Memory Painting: Harriet French Turner and Queena Stovall

Mar 09, 2019 – Aug 25, 2019

During the middle of the 20th century, a group of untrained women painters gained critical recognition for their works documenting day-to-day activities from their pasts. The most famous of these painters was Anna Robertson or “Grandma Moses,” but Virginia natives Harriet French Turner of Roanoke and Queena Stovall of Lynchburg were recognized for their lively, colorful depictions of their locale and memories. These women started to paint in their 60s, after having raised their families, and with recently gained time to reflect on their yesteryears.

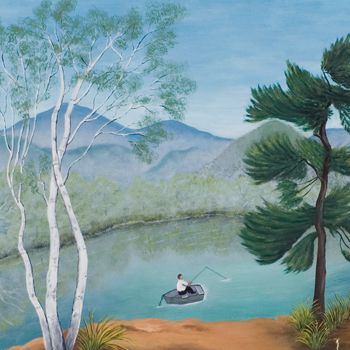

Harriet French Turner (1886–1967) was born in Giles County, Virginia, but moved with her family to Roanoke in her early teens. After completing high school there, she became a teacher, then married pharmacist James R. Turner. She then devoted her time to maintaining her household and family, though if she had any spare time she painted copies of artwork. Turner had very little formal art training — she had focused on music as an accomplishment — but picked up fundamental techniques from her sister who had studied art. After her husband’s death she focused increasingly upon her painting, and was inspired to paint her first original work, a landscape she could see from her home, for a juried art show held by the Roanoke Fine Arts Center (from which the Taubman Museum is descended). This work was in fact accepted into the exhibition.

After this success Turner turned to painting original compositions, mostly rural landscapes where human activity is secondary. In 1962, she became the first living artist to have a solo exhibition at the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center in Williamsburg, having previously been the subject of a documentary film by the Center’s filmmakers. Her paintings are in local private collections and museums, but also in the collections of the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, the Museum of American Folk Art in New York City, and the estate of Lady Bird Johnson.

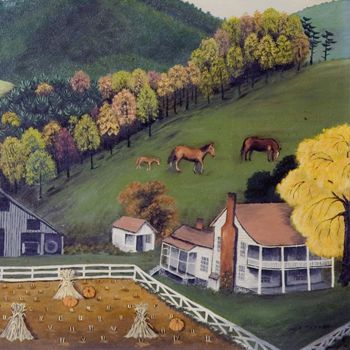

Emma Serena Dillard Stovall (1888–1980) was born in Amherst County, Virginia, and nicknamed “Queena” after mispronunciations of Serena. She married salesman Jonathan B. Stovall, and maintained two homes, a farm home near Elon, Virginia, during the growing season and one in Lynchburg during autumn and winter. Her children having grown up, Stovall decided to take an art class at Randolph-Macon Woman’s College (now Randolph University). Pierre Daura, internationally respected painter, was teaching that course, and encouraged Stovall to drop the class and develop her talent in her own style.

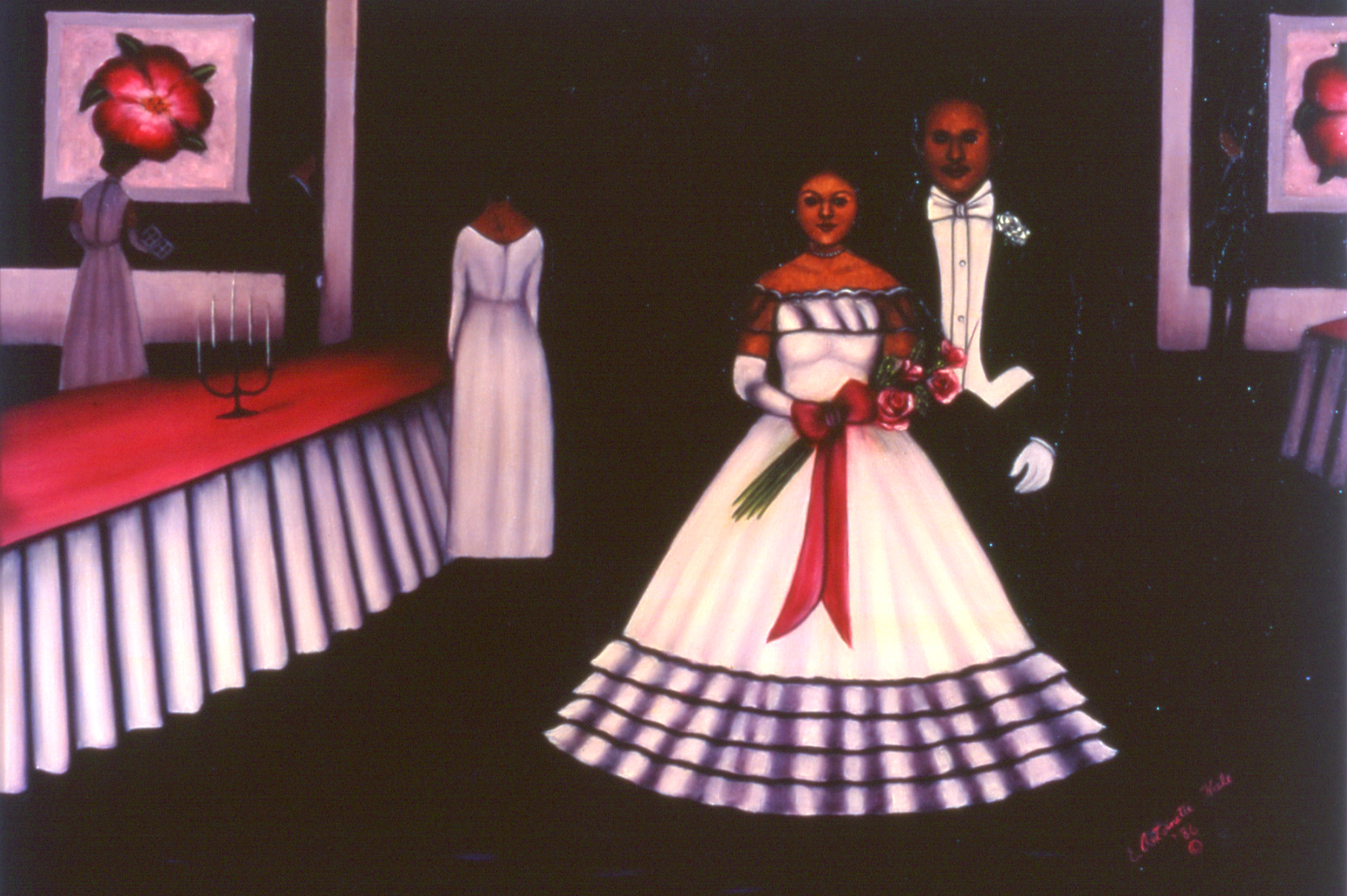

Whereas Harriet French Turner emphasizes the natural world in her painting, Queena Stovall’s subjects are most often people and their activities. She painted the rhythms of farm life as she remembered them. Her first solo exhibition in 1956 was at the Lynchburg Art Center; subsequently she was the subject of a 1974 traveling exhibition which was hosted at Lynchburg College, the Abby Aldrich Folk Art Museum in Williamsburg, Virginia, and the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, New York. Her work is in local museums and family collections, as well as in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and the Fenimore Art Museum.

It is important to note the respect shown by trained artists and scholars for these self-taught women artists, who moved against the abstract painting and philosophy so prevalent during the post-World War II period. Perhaps these women were seen as a counterbalance to the titanic compositions and conflicts explored in the largely male world of Abstract Expressionism, and to the changes at large in post-war America. Their work can be seen as a reflection of Turner’s and Stovall’s pasts, but must also be recognized as personal new beginnings, an establishment of late-life careers.